FINAL S4 | BUSINESS CASE SCENARIO 12

Submission BCS

Financing solar energy

Submission Date & Time: 2022-11-06 08:14:40

Event Name: NMO Season 4 Final

Solution Submitted By: Mansi ghegade

Assignment Taken

Finance AllocationCase Understanding

One of SELCO’s main goals is to dispel the myth that poor people cannot afford or maintain sustainable technologies. SELCO’s Senior Manager of Mission Projects, Prasanta Biswal, says, “We assume all too easily that the urban slum-dwellers are economically poor. The fact is that many of them are materially deprived. Their problem is one of access.” Recognizing this difference helped SELCO design a model that focused beyond provision of energy to the social impact of sustainable solar energy provision as well. SELCO has linked its consumers with loans for solar energy to increase access. The result has been an ushering in of financial inclusion for the urban poor that has further impacted their access to education and livelihoods. Solar lighting has helped individuals at the base of the pyramid improve productivity – in their work and study – without dependence on fuel-based options. For families who never had electricity in their homes, it represents a big improvement to their quality of life. Slum electrification, through active demonstration, has also helped improve awareness about solar power and increased acceptance of this unfamiliar technology.BCS Solution Summary

India’s urban poor are accustomed to going long hours without electricity. This impairs their ability to work or study after dark, making their climb out of poverty even more difficult. SELCO, founded in 1995, first started looking at the urban poor as a market in 2008, and found that what this group really lacked was access to finance-without which solar energy becomes unaffordable. The urban poor had no access to loans since they could not provide collateral. Mostly migrant laborers, the slum-dwellers come from different states in India and set up illegal housing on government land. On paper, SELCO’s urban poor market simply did not exist and had no identification to even attempt to apply for bank loans. The SELCO team’s first urban initiative in 2008 was focused on a slum of over 400 households in Manipal, a university town in Karnataka-the same state as SELCO’s home base of Bangalore. Though the slum-dwellers were employed and had earned income, their illegal settlement was not allowed to access “the grid” cables that crisscrossed overhead. Instead, families spent INR45 (US$1) per liter on kerosene-a financially unsustainable solution that could only be used for bare necessities such as cooking. Light for working or studying was a precious commodity. The SELCO team identified an interest and willingness among these slum-dwellers to pay for solar power systems in installments, but they clearly expressed an inability to pay INR6,000 (%7EUS$133) or more at one go. The systems installed in the slum households are priced between INR6,000 and INR11,000 (%7EUS$219) based on the number and types of lights installed.Solution

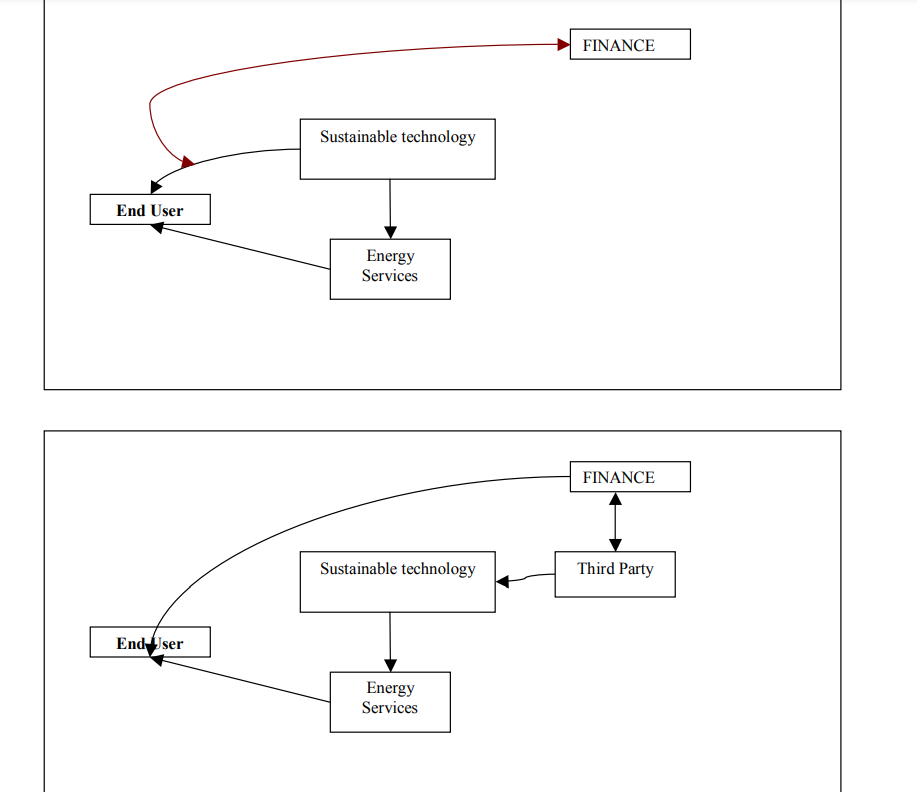

Loans were the solution, but the SELCO team found that it was very difficult to convince banks to lend to these households. In late 2009, they partnered with a small cooperative bank that loaned funds to small businesses in Manipal and who was willing to take a chance on expanding into solar financing for the poor. This was the bank’s first endeavor with solar and, therefore, it demanded a 100% guarantee from SELCO. In what was later seen as a turning point, SELCO agreed to offer a 100% guarantee for the first five systems priced at INR10,000 (%7EUS$222) each with a one-year deposit of INR50,000 (%7EUS$1,111) made to the bank. Remarkably, the entire repayment to the bank was completed within one year. The bank soon realized that this was a stable set of borrowers and offered to finance an additional five systems. This time, they went forward without a guarantee.

With the financing in place, SELCO solar powered 65 households, and the bank continued to provide loans to the slum-dwellers, even opening savings accounts and sending out a collection agent every week. Soon they had around 400 savings accounts with people saving sums ranging from INR50 (%7EUS$1) to INR 1,000 (%7E US$20) per week. The savings were no longer just for solar power alone; account-holders used their savings accounts to take out motorcycle loans, appliance loans and more. The SELCO financing model had resulted in financial inclusion that was powering many parts of their lives.

Scaling Slum Electrification

Since the Manipal pilot, SELCO has launched initiatives in other slums in the city and Bangalore as well. “The model is scalable, but it all depends on the financing. The nature of the slum community varies from slum to slum. Not all of them are reliable, and not all slum-dwellers stay in the same slum for long durations of time. Slums are demolished and relocated.”

Scaling up challenges ranged from poor financial literacy to simply not having considered an alternative to expensive and unsustainable firewood or kerosene. In a second slum, for instance, repayment was poor in the first month. The SELCO team discovered that this was because the borrowers were financially illiterate and felt they could pay the installments at any time that was convenient. SELCO and the bank helped with some basic financial literacy training to drive home the importance of regular payments. The bank agent even brought an ATM to the slum households and collected the payments strategically on the day after pay day, reducing he likelihood of default.

With experience, the SELCO team found ways to dig deeper and define affordability to the urban poor. They found out that in a typical urban slum household of five members, expenditure on firewood amounted to INR450 – 600 (US$9 – US$12) in addition to the cost of 10-15 liters of kerosene at the rate of INR 45/liter. Families were more than happy to consider paying for solar power in regular installments that matched this amount. Taking the unique circumstances of each community into consideration, the SELCO team works out a plan that suits both the bankers and the borrowers.

For a solution to the unreliability and non availability of power,the villagers approached SELCO for a solution. SELCO, along with financial partner Cauvery Kalpatharu Grameen Bank (CKGB)demonstrated solar as a solution by bringing in a package of doorstep technology and financing.

CKGB agreed to finance the systems but through groups of ten families forming a Joint Liability Group (JLG) which would in turn receives financing from the bank.The primary characteristic of the JLG is that each family will be equally liable for the loan thereby socially pressurizing each other to ensure timely repayments but it is different from the more commonly known self-help group as a JLG will not earn any income from facilitating the financing.The demonstration and transaction costs of creating JLGs were facilitated via REEEP support. Today, 28 families own a solar home LED lighting system. Due to their proximity to the National Park, many residents describe a life of constant human-animal conflict with the common presence of elephants, leopards, monkeys and other wildlife destroying crops and killing cattle. Fearful of the unpredictable danger in the night many villagers were confined to their homes from earlye vening.The lights have become a source of security, deterring animals from venturing too close to their homes.The visionary leadership of the bank coupled with SELCO’s mission of providing sustainable energy to the underserved has ensured that at least these 28 families are not fearful of the darkness anymore.

Karwar is one of the major ports of Karnataka catering to the Northern part of the state,Goa and Southern Maharastra.It is probably better known as the host of one of the main nuclear power plants, Kaiga, in India.The bustling fisheries industry along the Indian coastline is a source of income for a sizable portion of the country’s population. Several income groups benefit from this multilayered industry ranging from catching fish, segregation, processing,storage and sales.The fishermen community are a vulnerable lot whose livelihood is prone to unpredictability and natural disasters as many live along the sea coast.A typical home for members of this community is a makeshift shanty which serves as a migratory shelter usually along the sea coast.Access to any basic amenity such as electricity, sanitation,or drinking water is a luxury.

It is one such community,primarily in the business of selling fish,that SELCO staff happened to pass by in August 2009 and subsequently stopped as they noticed that their households did not have any access to electricity.Initially there was widespread apprehension in this community of nine households over the reliability and cost of a solar system.Despite several visits after this first contact the community was still unsure about the benefits despite being completely unelectrified without the prospect of grid connectivity in the near future.SELCO then installed a solar lighting demonstration unit at a local restaurant which was strategically chosen due to the constant flow of people.

Lack of awareness of how the light works on solar energy was further complicated by financial barriers as their settlements were migratory in nature: makeshift shanties without legal land documents, hence none had access to a institutional financing. Despite approaching banks in the area there were concerns that repayment would be risky given the nature of the customers. One such bank was Karnataka Vikas Grameen Bank who nurtures a 15 year partnership with SELCO.The local branch manager was still doubtful about the repayment capacity of the community. Leveraging SELCO’s previous successful collaborations with KVGB, using REEEP support to cover the initial downpayment and transaction costs, the SELCO staff approached a senior manager at a nearby town to intervene and convince his colleague about the project. One telephone call later,the Karwar KVGB office told SELCO it would be willing to finance the fishermen community as part of their financial inclusion portfolio. The financial barrier of downpayment was overcome by using REEEP support. However in order to avail the loan certain bank charges were mandatory as part of the documentation process.This once again raked up hesitation within the interested families who were themselves interacting with a bank for the first time. Upon understanding their concerns, SELCO offered to channelize more funds towards the downpayment so that the pinch of paying for the paperwork for the loan was subsided. It would have been easier for SELCO to directly pay for the documentation but it was important to encourage the community to experience the workings of a bank and in turn their procedures.Subsequently,2-light home LED systems were installed primarily to meet their domestic purposes. Bordered by the sea at one side and a long stretch of road on the other,the darkness is even starker at night.The families insist that the lights have now made them feel like they are living in a house.The process of getting these lights has also made them feel ownership.For all,the first time experience of walking into a bank and processing documentation for a loan instilled a confidence in them.Today,many of them speak of opening savings accounts and availing more loans.This for SELCO goes beyond just providing a light but also enhancing the quality of life of the fisherfolk.

Sonalhadi is a tiny hamlet of eight houses which has no access to conventional grid electricity.The villagers are originally from the Kuruva tribe and used to source their income traditionally as hunter-gatherers. However,with the introduction of wildlife protections laws they had to find an alternative as daily agricultural labourers with their own basic needs being sustained through produce from small agricultural plots allotted by the government during the transition. On one of their travels, SELCO staff heard about the village. Upon further discussions with the community it became increasingly clear that decentralised lighting via solar made sense provided affordable financing was in place. SELCO then approached its financial partner, Cauvery Kalpatharu Grameen Bank (CKGB),to provide financing to the community. The local branch manager of the bank took an active interest and personally visited the tiny hamlet with SELCO staff and instilled a sense of financial confidence in the people encouraging them to form Joint Liability Groups (JLG) as a first step for the bank to facilitate financing. REEEP support was used to facilitate the transaction costs involved in generating awareness within the community. Subsequently the villagers were convinced about the JLG model of financing. CKGB then financed the LED solar home lighting systems for eight households through the same model. The villagers today enjoy four hours of lighting in the evening when they need it the most.With the purchase of solar lights these villagers are one step closer to enhancing their quality of life within their remote settings.

Conclusion

Since its initial pilot initiatives, SELCO has had an easier time establishing collaborations with local banks for financing, and the banks, in turn, have devised innovative ways of working with their new customer base. Biswal adds that banks are leveraging technology to allow urban poor people to repay loans or save even when they relocate to other slums or if their slums are destroyed. The Unique Identification Program (UID) program, he says, will help strengthen a bank’s ability to know its borrowers better and to help organizations like SELCO provide services to the poor with unstable or unsettled homes. SELCO’s strengths stem from its ability to look for unconventional solutions and focus on the final outcome. Says Biswal, “It is not about financing just solar power. When we convince banks who are perhaps happier to fund business loans as it is directly income generating, we talk to them of how solar energy empowers the urban poor to spend an additional couple of hours after dark in income generating activities such as beedi (cigarettes) or agarbatti (incense sticks) rolling.” The SELCO model of delivering affordable products and services to the poor – and consciously multiplying social impact – is one that can easily be adopted by organizations who are seeking to achieve sustainability with social impact and financial inclusion. Dr. Harish Hande, SELCO’s Managing Director and this year’s Ramon Magsaysay Award winner, says that his company looks at scaling up differently. They are focused on replicating and incubating more SELCOs rather than building a huge geographical footprint. ’SELCO people,’ as they are proud to be known as, have a different philosophy on responsibility: their job does not end with a sale – it is a long-term relationship they share with the underserved, which grows as they are empowered through financial inclusion, education and livelihoods.Comments

Article Type: Business Case Scenario, Case Study Solution Submission

Business Case Detail

Title: FINAL S4 | BUSINESS CASE SCENARIO 12

Type: Case Study

Stream: Management

Participant

I am bms graduat student from navi mumbai currently pursuing MBA from pune University

Team Nicolaus

Total Team Points: 144735